Lisa Lane, 1933-2024

It's late at night at the Marshall Chess Club in New York City, early 1960s. Smoke wafts between shadowed men playing chess under lamplights. But what stands out most in this historic photograph is the sole young woman, exhaling the fog of war over an illuminated chessboard as she prepares to move a black piece.

She won her first U.S. Women's Championship two years after learning the rules of the game.

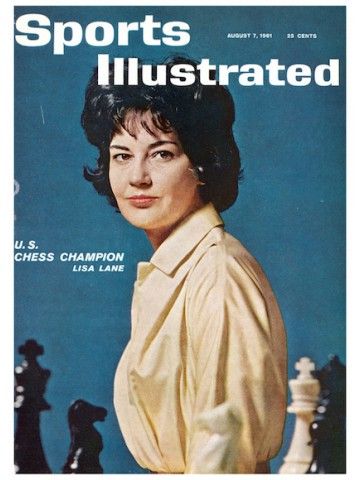

Two-time U.S. Women's Champion and WIM Lisa Lane was one of the first women chess players to attract popular media attention in the United States to what's sometimes called "the game of kings." She was the first chess player, of any gender, to be featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1961, over a decade before GM Bobby Fischer did in 1972. She died on February 28, 2024, in Carmel, New York, at the age of 90. Her death was confirmed by the town clerk's office in Kent, New York.

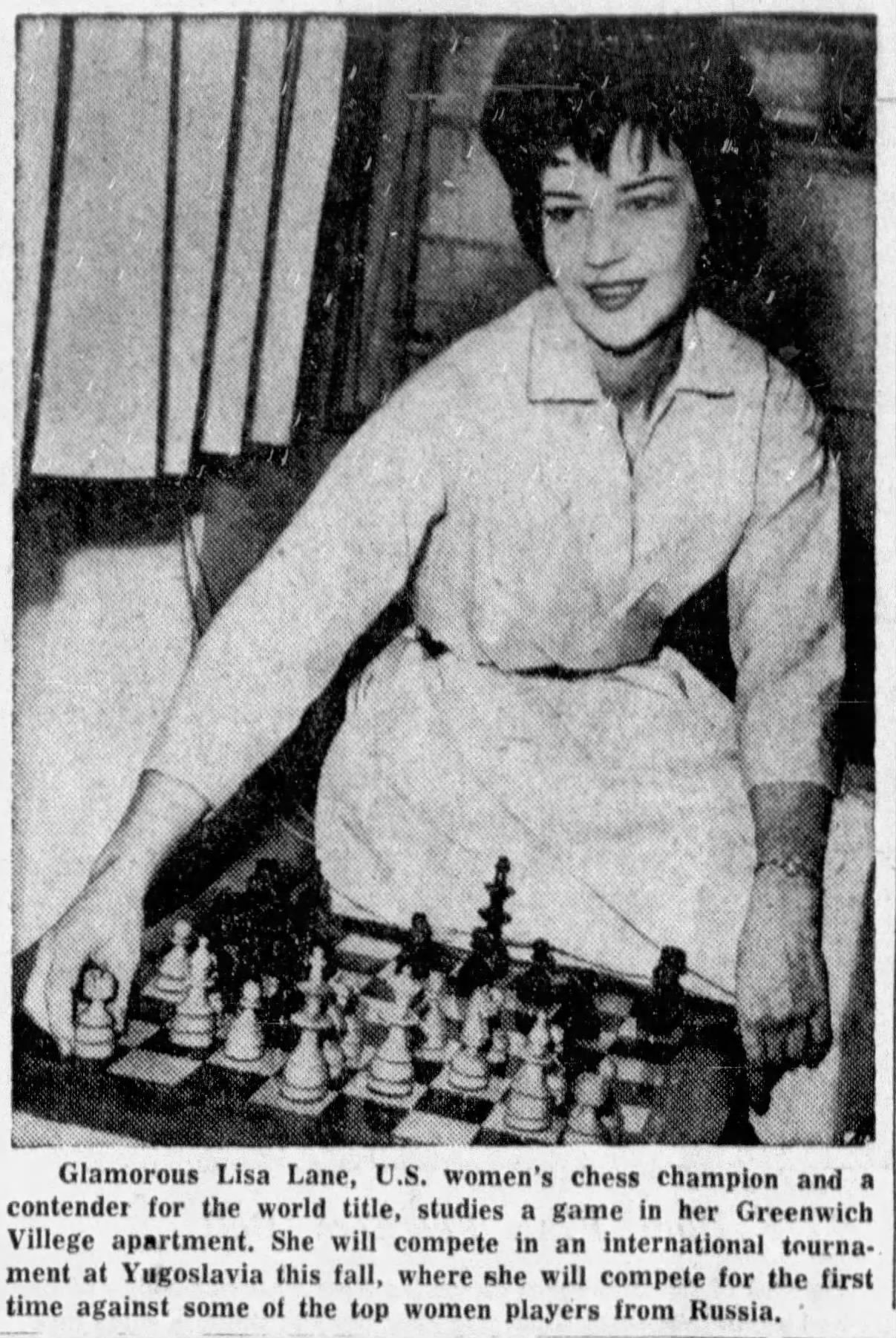

"Lisa Lane showed the world that chess can be glamorous and that women can be as competitive as men," wrote WGM Jennifer Shahade in her book Chess Queens. The glamor cut both ways: media often fixated on her physical appearance and personal life, with chess being a secondary point of interest. That first Sports Illustrated piece focused on her presence at the board: "At such moments she seems a very serious young woman, but beautifully serious, or seriously beautiful, a side of feminine loveliness that Hollywood has rather neglected." This kind of depiction would follow her for about a decade in written and televised media coverage.

In the limelight, she was also an early advocate for equal pay and recognition of women in chess. "I'm the most important American chess player," she told The Times in 1961. "People will be attracted to the game by a young, pretty girl. That's why chess should support me. I'm bringing it publicity, and ultimately, money."

Lisa Lane showed the world that chess can be glamorous and that women can be as competitive as men.

—Jennifer Shahade

Lisa Lane, the first chess player to make the cover. Photo: August 7, 1961 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Lisa Lane, the first chess player to make the cover. Photo: August 7, 1961 cover of Sports Illustrated.

NM Bruce Pandolfini, who brushed paths with Lane around three times across the 1960s and 70s, told me: "She was certainly, in America, the second-best-known chess player. Not around the world, but after Bobby Fischer, ordinary [U.S.] citizens probably knew her before anybody else." He called her "a real chess icon."

As U.S. women's champion, she'd appeared on television several times. On To Tell the Truth in 1960, four panelists had to discern who was the real Lisa Lane among three women by asking a series of questions. Selecting the right one from the impostors, panelist Kitty Carlisle remarked: "She's awfully pretty to have devoted eight to 10 hours to chess!"

She's awfully pretty to have devoted eight to 10 hours to chess!

—Kitty Carlisle, To Tell the Truth

In 1961, on the CBS game show What's My Line?, a panel of men had to guess her occupation. National chess champion didn't come up, and a panelist said: "Because she’s so pretty, we ruled out anything intellectual.” In the 60s, this sentiment would reiterate itself in different ways: that her appearance and chess ability were astonishingly incompatible.

She attracted plenty of attention. “I get a lot of love letters from other chess players,” she told Sports Illustrated. “I read them, I laugh, and then I file them. Letters from grandmasters go on top.”

I read them, I laugh, and then I file them. Letters from grandmasters go on top.

—Lisa Lane

Shahade told me:

She had this love-hate relationship with the media and the press. On the one hand, she was open about the fact that she deserved to get a lot of attention because she was bringing so many more people into the sport... this, in addition to her equal pay initiative, was ahead of her time.... She embraced it on one level, but then on the other hand, she also seemed to get annoyed by the repetition of the questions, not just from the media but from the public at large.

She had this love-hate relationship with the media and the press.

—Jennifer Shahade

The publicity that followed her did bring more attention to chess, but it also came at the cost of repetitive (at best) and sexist (at worst) questions. Mixed in with the furor about her looks was the phrase, "She plays like a man!"

In the post-2020 era, it's tempting to draw a parallel between Lane and the fictional character Beth Harmon from the Queen's Gambit. The charming girl who navigated a sport dominated by men, who became a champion just a few years after learning the rules—Lane really did these things. But it may be a stretch to say she was the model for Harmon.

Walter Tevis, the author of the book the Netflix show was based on, claimed that Harmon wasn't based on any specific person. Pandolfini, who worked with Tevis on the novel in 1982 before it was published and also consulted for the Netflix series production, said the book's author was certainly aware of Lane, GM Nona Gaprindashvili, Vera Menchik, WIM Rachel Crotto, and WIM Gisela Kahn Gresser.

But he also said: "The Beth Harmon of the novel is not Lisa Lane. Lisa Lane was very attractive, very glamorous. Beth Harmon is not glamorous in the novel. She is in the Netflix series... but we shouldn't confuse the two characters. They are different." Putting aside the original novel, the Netflix series does portray Harmon as a strong and glamorous chess player.

There are clear differences between Lane and Harmon too: Lane wasn't an orphan, did not play a world champion in a formal game, and didn't suffer from substance abuse, for example.

She was born Marianne Elizabeth Lane on April 25, 1933, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her mother worked two jobs and Lane never knew her father, a leather glazer and horseracing enthusiast who left before she turned two. She and her sister, Evelyn, boarded with many families and frequently changed schools.

After completing two years of high school, she dropped out. During the period that followed, she said she'd held 13 jobs in a matter of two years. Feeling out of place among the highly educated friends of her boyfriend at the time (an older man), she enrolled as a special student at Temple University, and she mostly took high school classes there.

That relationship ended, and in the spring of 1957, she discovered chess while on a date in a coffee shop called the Artists' Hut. She would have been 23 or 24 years old, a late bloomer—though she herself erroneously recalled being 19 at that time. She played there regularly and met Arnold Chertkof, who introduced her to Attilio di Camillo, a top U.S. player. She caught the chess fever, and he taught her.

She studied up to 12 hours a day and played chess all the time. She was fiercely competitive and hot-tempered ("I hate anyone who beats me," she once said). At the Franklin-Mercantile Chess Club, she was accused of throwing an ashtray at someone after a game. She rebutted: "I never hit that guy with an ashtray." Apparently, she threw it at the table, not him, and it happened to break, and a piece flew up and hit him. Collateral damage.

I never hit that guy with an ashtray.

—Lisa Lane

In late 1957, Di Camillo left to play the U.S. Championship in New York and invited Lane along. She closed the poetry shop she'd opened in central Philadelphia and went. In fact, 14-year-old Fischer won his first national title at this tournament, beating Di Camillo along the way. Lane later became friends with Fischer, who'd visit her apartment in Greenwich Village to play chess.

Di Camillo told her: "If you're willing to work, you can be the women's champion in two years." Except for a matter of a few days, she became champion almost exactly two years later.

If you're willing to work, you can be the women's champion in two years.

—Attilio di Camillo

She won the U.S. Women's Championship in 1959 and would hold onto it until 1962, when Gresser regained the title for the fifth time (of nine total). She'd tie for first with Gresser in 1966 for her second title. As U.S. women's champion, she participated in the 1961 Women's Candidates Tournament (finished 13th) as well as the Candidates in 1964 (finished 12th). She was also on the U.S. women's team in the 1966 Women's Chess Olympiad.

She was one of the very best women players of her time in the U.S. Though she didn't quite break into the top of the world stage, her stardom inspired girls who would read about her. Diana Lanni, for example, spoke about Lane's influence on her explicitly in Chess Queens.

Lane married twice. She first married Walter Rich, who worked in advertising, nine days after becoming U.S. women's champion, but divorced less than two years later. Her second marriage, to Neil Hickey, a reporter who interviewed her for The American Weekly, caused an uproar. In 1962, she dropped out of the Hastings International Chess Congress mid-tournament, saying she couldn't concentrate because she was in love. Tabloids were all over it in Europe and the U.S., with a Daily Mirror headline reading "WOMEN CAN'T FORGET THE LOVE GAME," and she was met back in New York with a barrage of newspaper reporters.

Lane was frustrated with the lack of funding and opportunities for women in chess on several occassions. In 1963, she wasn't invited to attend the Women's Chess Olympiad. Customarily, the top two women were, and she was second behind Gresser. The reason was that Gresser and Mary Bain, a lower-rated woman player, could afford the expenses on their own. “Since when did you have to be a millionairess to represent your country in sport?” Lane asked the Associated Press after her spot was taken.

Since when did you have to be a millionairess to represent your country in sport?

—Lisa Lane

In 1966, the first prize for the U.S. Women's Championship was merely $600, compared to $6,000 in the main event. She recruited several men from her chess club ("The Queen's Pawn," which she opened in Greenwich Village) for a protest, with one sign, among others, reading "One Man Is Worth Ten Women?" But the protest was largely unnoticed, and other women didn't join in.

She became disenchanted with chess, or at least organized chess. And so, at the age of 33, she left it. Lane told Shahade decades later: "I don't think the things I did in chess forty years ago are the most important things in my life" and "I guess I was good copy."

Shahade, for this article, told me: "She was ahead of her time. It just wasn't necessarily the right time for her to be in chess. First of all, there was the equal pay and the lack of respect for women, but then there also just wasn't enough respect for the publicity initiative that she was doing. It was huge, and it didn't seem like people cared as much as they should have."

She was ahead of her time. It just wasn't necessarily the right time for her to be in chess.

—Jennifer Shahade

She and Hickey moved upstate, where she ran a health food store in Carmel, New York. They had no children, and he died three weeks after she did. She was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in 2023.

Lane told Sports Illustrated in 1961: "It sounds foolish to say it... because even the best men players don't seem to be able to make their living by chess, and no woman ever has. But I think that I may be able to do so, and at least someone should try."